Celebrating what it means to have a ‘safe space’ after experiencing loss

Although it is a universal experience, the grief process can be complicated. Here, I present a journalistic experiment and different approach to surviving grief by celebrating what it means to have a “safe space.”

I wanted to see if my art could help other people combat the complicated experience of loss in the same way it helped me. While studies show doing art can help people take their mind off grief, according to the Hospice of the Piedmont in Virginia, landscape paintings on their own can generate feelings of calmness.

A safe space is a place or environment free of harm, encouraging someone to feel safe and present in the moment. By providing a creative interpretation of their safe spaces based on written responses, I hoped to help capture this for the people I interviewed. This story is not what you’ll find in typical journalism that leads to people reliving their loss. Instead, it’s about how people are moving on through these safe spaces, not about what caused their grief or what they have been through.

To learn how spaces can take people’s minds off grief, I sent out a request on social media targeted to young people, a group particularly vulnerable to the developmental effects of grief according to the National Library of Medicine in the United States. Four people between the ages of 21 and 23 shared their experiences with me and allowed me to paint their safe spaces.

Talking about grief can help combat the stigma surrounding it, according to the Mayo Clinic. My experiment/story was designed to open up the conversation about loss, hopefully inspiring people to talk about their experiences, share tools to help with grief and provide support to others in their own communities. The first step was to capture my own safe space.

Dead-end road

My safe space is a dead-end road in the Halton Region with an entrance to an unmarked trail. Tree roots protrude out of the ground and the path is slippery when it snows, but I’ve loved it for years. I can’t remember the first time I drove to this windy dead-end road, or count the times I visited, but it’s a space that brought me wonder when I needed it most. I bring friends and family there but I also go there to reflect alone.

Since 2020, I have lost multiple family members to illness and death and experienced additional non-death related forms of loss and change. The loss of my childhood dog, Riley, in March 2023 made me realize I felt completely desensitized to loss and had been shutting out the world around me.

In my most recent trip I drove to the dead-end road eagerly anticipating its absence of dog-walkers and hikers. It was a cold day. I travelled in light layers unsure of how far I’d walk in the heavy snow. My feet crunched in the snow and I crouched down to watch a tiny stream flow that I had never noticed before. The dark water trickled down the path and that’s all I could hear. I focused intently on the ground I was standing on. I remembered I was still alive, and it was my responsibility to celebrate that.

The need for support

There is a current need to explore different ways of dealing with grief because it is so difficult to get help. A large challenge surrounding grief comes from a lack of support. In Canada, the average wait time for community mental health counselling is 22 days, according to a 2020 report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

How can we fulfill the need for better grief support and tools? Susan Cadell, a professor of social work at the University of Waterloo, said more education is needed at all levels to de-stigmatize grief. “As children develop and understand, they develop different understandings,” she said, adding, “The loss of a friend, for instance, when you’re five is very different from when you’re 15 or 25.” Re-experiencing grief and experiencing it differently at various ages demonstrates this need for continued education.

Cadell said young people are particularly vulnerable to grief because of the ways people have moved away from tradition and its outward, prescribed rituals surrounding funerals. Questions of what to wear to a funeral, how to behave, etc. are less talked about today, leaving young people to experience grief without much prior knowledge or support. With more talk about funerals, Cadell said, the better people can understand other experiences of loss.

“Grief is important because it happens to everyone in some form or another,” Cadell said. It is a reaction to loss, and although it can occur from the death of a person, it can also come from things like the loss of a job, the loss of identity, divorce, being adopted or graduating school and losing the identity of being a student. “Loss is ubiquitous although we tend not to acknowledge it,” she said.

An important distinction in the world of loss is between grief and trauma. According to The Grief Recovery method, trauma is an event and grief is a natural response to loss. Although it might feel inconvenient to everyday life, grief is not an unnatural thing. “Hopefully we can prevent trauma from happening, whereas we’re not ever going to prevent grief from happening,” Cadell said.

Art and grief

What I’m doing journalistically is building on the work of other artists who are using their work to explore feelings associated with loss and change. Since we can’t prevent grief from happening, can we find healing through the images we see?

Shelley Vanderbyl, a Canadian conceptual artist, explores this question through storytelling in her work. Experiences of loss, change and her fight against cancer are some of Vanderbyl’s motivations behind her wide array of expressive projects.

“There are a few ways that art can help us with the experience of grief. One is that while we are experiencing a void, creating something new in the presence of the emptiness can be cathartic,” she said.

One of her most recent projects is “Medicine Tins.” It is a series of tiny landscapes and scenes painted in small vintage medicine tins to promote the idea of art as medicine. The tins are gifted, sold and exhibited to help open conversations about mental health and healing.

During Vanderbyl’s recovery from cancer, she would paint in bed. “Throughout whatever I was experiencing, I was still able to make the medicine tins,” she said in an artist’s talk on Nov. 16, 2023. “I sort of used myself as a test subject, that if I found this beautiful, if this is what I really wanted when I was really stressed, then maybe it will help someone else too.”

When it comes to grief and hardship, Vanderbyl said, “Art allows us to re-narrate or retell events as a story, to bring a more satisfying ending or sense of closure to an experience that felt harsh or abrupt. It can give us a sense of control, when life feels out of control.”

When it comes to opening up conversations about grief and mental health, Vanderbyl said, “I think art can be a bridge.”

“Rather than definitively saying what a painting is about, I like to have conversations by saying, ‘here’s what it makes me think of, or here’s what this brings up for me.’ It can create a really open environment that allows for healing to occur,” she said.

Safe spaces

To Cadell, safe spaces can be a place to sit and think about grief or not think about it at all, depending on the person and the moment. “A safe space might be being alone, but it might not be,” she said. Out of the four respondents to my survey, two of them noted other people in their safe spaces with them. Safety is also accessible in communities with things like online and in-person support groups, or social settings that help a person feel present. With grief, Cadell said, “You don’t have to be alone.”

“Grief is really hard, and it can be beautiful as well – and we have to be able to hold both of those when we are both experiencing grief and with dealing with someone who’s grieving,” added Cadell. Dealing with grief requires self-compassion and social acts. With this balance of self-compassion and outreach for support in mind, I painted the safe spaces shared with me, transforming them into art.

Lambton Woods, Etobicoke

Julia McGolrick is a fourth-year English student at Toronto Metropolitan University who allowed me to paint and share their safe space. In my initial inquiry, Julia said her space helps take her mind off grief and hardship. Julia’s space is a path in Lambton Woods, Etobicoke, that she said feels like it “never ends.” But she likes to share this space: “I felt very safe knowing that I was with someone I admire and on such a beautiful path that stretches on forever.” Knowing this place exists provides her comfort. She said, “I now know I can return there whenever I need a breath of fresh air/a space to take my mind off things.”

Painting Julia’s scene reminded me of walking through trails, feeling curious about what I might discover. Lambton Woods, like many trails, has multiple bridges, twists and turns. To translate the feeling of wonder, I created my own version of a bridge in a scene inspired by Julia’s experience of the seemingly endless woods.

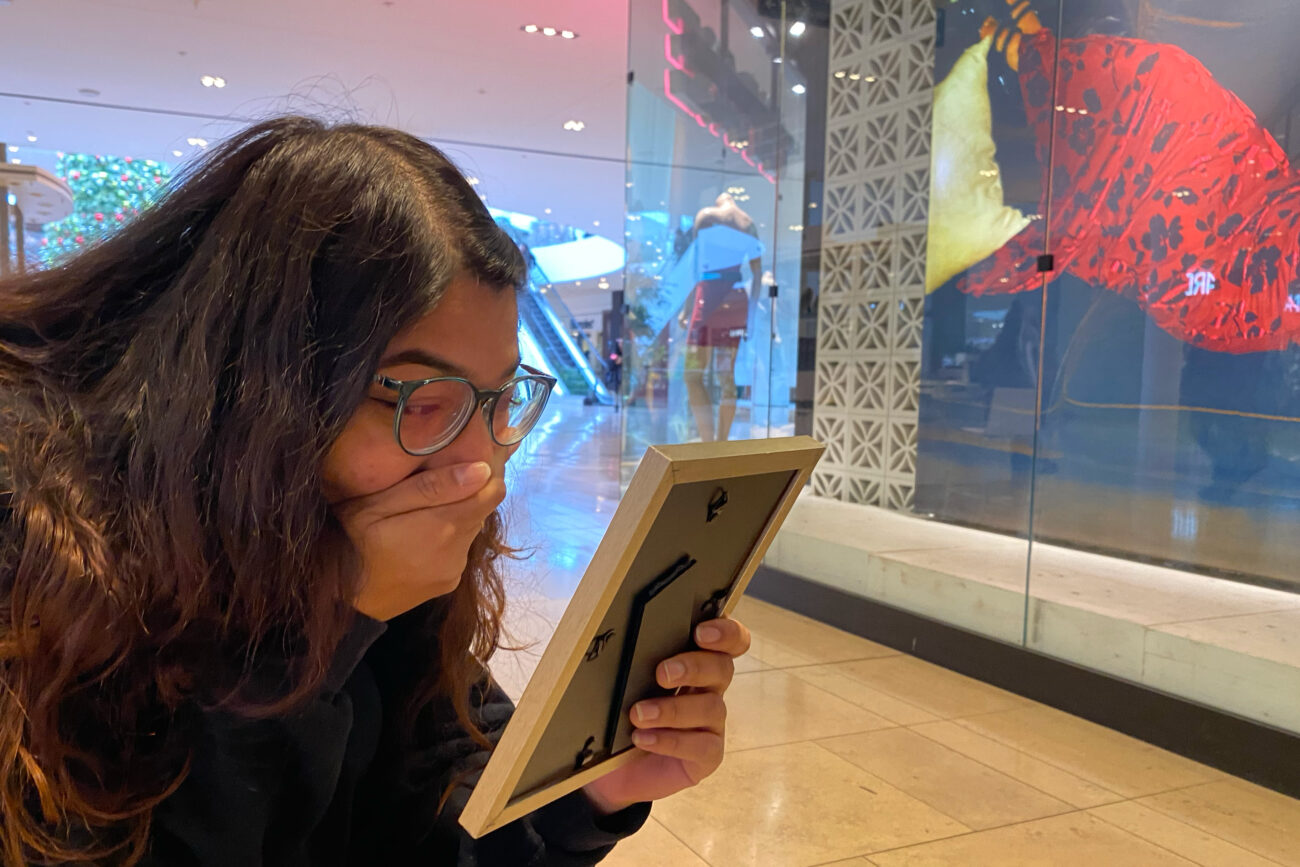

I met with Julia on Nov. 30 to give her her painting. She wrote to me afterwards and said, “Receiving my safe space painting was amazing, I was totally awestruck. As soon as I saw it I knew it resembled the space perfectly, and captured its essence. I got the same serene feeling that I get while being in the actual park just by looking at the painted version.”

Julia said she plans to clear a space on her desk for it: “I would like to have it isolated, perhaps with a few candles nearby for decor. Although this piece is so gorgeous it speaks for itself.

Hungry Hollow Trail

Hungry Hollow Trail in Georgetown, Ont., is the safe space for Giuliana Piscione, a student at the University of Toronto. After a car accident, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Guiliana was stuck in bed recovering. “As soon as I was able to start walking again my boyfriend would take me there to get out of the house and just get fresh air,” Giuliana said.

For Giuliana, Hungry Hollow Trail was “a space to grieve the way things used to be before the accident,” and also a place to appreciate “still being alive.”

“It was scary for me to get in the car again and it was also scary to be away from home with a surgical wound still closing and healing,” Giuliana said. Her boyfriend was one of the only people she felt comfortable getting in a car with, feeling safe around him while also connecting to the nature around her. The trail wasn’t too far from home for Giuliana.

“This spot has become a routine place where we walk often, snow or shine,” she said. “We visit during every season to enjoy the outdoors but also when we need a break from the day or the end of a long week.”

Giuliana received her safe space painting on Dec. 6.“ My experience with my painting created a whole new dynamic of ‘safe space.’ It provided me with an embracing feeling, and it brought so much joy and love into my heart,” she said after our meeting.

The painting is now placed on Giuliana’s bookshelf with her other treasures like books, crocheting supplies, and a photo of her and her boyfriend. “The painting and the portrait of us reflect our relationship and all the barriers we overcame as a team at the start of our relationship due to my injuries, both physical and emotional from the car accident,” she said.

Looking to the future, Giuliana said, “I plan to bring this painting with me wherever I go as not only a representation of my ‘safe space’ but also a reminder of the solace whenever I am faced with challenging scenarios I might face in the future.”

When painting Giuliana’s safe space, I wanted to celebrate her experience of recovery. I incorporated a long, winding bridge and tall trees standing tall above blue water to capture the natural elements that help make her feel present.

Tia’s Room

Tia is another young woman who has experienced grief and openly shared details about their safe space with me. After leaving home, Tia learned to manage her grief and loss by transforming her current bedroom into a place of safety, designed and curated by her to suit her personality. She described her room as having a bed in the corner with manga panels, “anime stuff,” fairy lights and printed pictures of all the people she loves and notes and cards she’s received from people over the last two years.

Entering a space as intimate as Tia’s, I found myself painting details I knew from her description but also added additional interpretations. Tucked in the corner of one of the reference photos she sent me was a keyboard piano. Although it wouldn’t be visible given the angle I decided to paint, I moved it into the frame to include more of Tia’s hobbies.

I don’t often paint interior scenes, so Tia’s safe space description allowed me to step out of my comfort zone and focus more on shape, perspective and value tones. Part of this experiment is learning about other people’s ideas of safety, and this painting reminds me of my own bedroom, which has also been a safe space for me. The bedroom can act as a self-portrait and this painting allowed me to think about the places we know so well, and how to transform intimate places into art.

Tia met me on December 7 to receive her safe space painting. “I love that you have captured it right after I have gone through such a difficult time,” she said. “Now I finally feel like I have turned a new page and things are the same, but like, better,” she added.

Tia reclaimed her space after experiencing difficult changes, turning her bedroom into a place filled with the things she loves. “Now it is mine and no one can take that away from me,” she said.

The Hundred Acre Woods

Tasha Budhai’s safe space from grief and loss is the fictional Hundred Acre Woods. The fourth-year journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University said imagining herself in a forest setting brings her the most peace. “Winnie the Pooh is and always has been my favorite Disney classic since I was a little girl and now, so the Hundred Acre Woods, the setting in which they live, is my safe space and where I imagine myself to be a lot,” Tasha said.

“Even though it is a fictional setting, the storyline is just as real and it makes me feel calm and safe. It makes my inner child very happy and takes me to a great place,” she added. Tasha’s is the only space from the people I talked to that’s imaginary. By linking her present day to her memories of childhood, I was able to tap into the aspect of imagination while painting.

I am also familiar with the warmth of the imaginary Hundred Acre Woods from seeing it in books and on television as a child. Tuning into that feeling of warmth, I decided to use bolder colours like red and yellow so the nature in the painting welcomes whoever else wishes to imagine the woods. For Tasha, I wanted to emit the feeling of home in a new place she can now visit with her physical painting.

I gave Tasha her “Hundred Acre Woods” painting on Dec. 4. Tasha told me afterward, “It exactly resembled that of the Disney classic so overall the experience was really great and it meant a lot to me.” She also said the painting represents her safe space and brings similar feelings of comfort.

Continuing the conversation

Looking back at my overall goal to celebrate people’s safe spaces, I hope to continue opening up the conversation about grief and loss. Some of the respondents have begun sharing their paintings on social media, and all of them expressed gratitude for the physical representations of their special places.

Both creating and viewing art can help people move on from grief because they involve focus and being present and engaged. As Shelley Vanderbyl said,

“Viewing art can be therapeutic for grievers, as much of the grief experience can be unfamiliar, new territory, or feel as though, according to their previous experiences, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. Engaging with things that are less cerebral and more spiritual or emotional can make more sense. Art-viewing can help calm the viewer. ”

As for my own safe space painting, I feel thankful to have had the time to reflect on all the changes and loss I have faced in the recent years by sitting down and recreating the space on canvas. I look forward to watching myself grow and recover alongside a community of people seemingly looking to do the same.