Microplastics In The Digestive System

The connection between microplastics and IBD, as told from the perspectives of experts, research reports, and those living with Crohn’s disease.

I’m one of about 322,600 people in Canada who have IBD. That figure is expected to rise to about 470,000 in 2035, exactly a decade away. One of the reasons for that increase could be microplastics.

I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, a kind of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), in 2023. Hearing the news, lying in that hospital bed still groggy from the sedation I was under for my colonoscopy, with my gastroenterologist hovering over one shoulder and my parents over the other, it felt like my world shifted. I lay there silently, blinking back tears, and trying to grasp my new reality.

I would have to make some changes to my life—routinely taking medication, changing my eating habits, being more careful and more conscious about what I was putting into my body. It’s different for everybody. For example, Robert, a man living with Crohn’s disease for 37 years, initially had to completely cut out fast-food and alcohol to try to preserve his intestines when diagnosed at 18. Jody, a woman diagnosed with Crohn’s at 25, was initially taking over twenty pills a day, trying to find a medication that worked to lessen her symptoms.

I’ve withheld both Robert and Jody’s last names here to preserve their privacy.

Robert tells me more about his process of getting diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, including medication, surgeries, and getting an ostomy.

Today, most people with the disease are recommended biologic medicines to take away their Crohn’s symptoms, including Remicade. It’s taken as a two to three hour-long drug transfusion that needs to be completed at a clinic about every eight weeks. There’s also Humira, which is taken as an EpiPen-like injection every two weeks.

This piece from the Canadian Digestive Health Foundation, written by Deanna Veloce, a registered dietician, describes many of my own feelings about the disease. Those include being vulnerable and embarrassed about what the disease entails, and even jealous and angry with people who are able to lead seemingly normal lives — not bogged down by exhaustion, weight and hair loss, no appetite, and other physical ailments that can cause incredible loneliness and isolation from the rest of society.

Medication is a lifesaver, truly, but it doesn’t change the fact that this condition is forever. That means you can either try not to think about it, or try to understand it, thereby learning to accept and live with it.

Robert talks about the way his body changed after being diagnosed with Crohn’s.

During some early research into Crohn’s, I found several articles claiming that one factor for the disease’s development could be environmental pollution, specifically plastic pollution – and that includes microplastics.

The causes and effects of microplastics on IBD are still unclear, as it’s a fairly new field of research. However, some experts are finding evidence there could be a connection.

What Are Microplastics?

Microplastics are microparticles of plastic that make their way into environmental settings, like oceans, through the decomposition of packaging containers and clothing, alongside other pollutant materials. Nanoplastics are very similar to microplastics, but even smaller, typically less than one single micron each, hardly visible unless you use magnification techniques. They are smaller than the width of a strand of human hair, or practically invisible.

While there is no scientifically agreed-upon definition for the term, microplastics encapsulate various sizes, shapes, structures, colours, and origins of plastic that are broken down into smaller components. These components present threats to various communities, including sea creatures, animals, and humans. They’re in the gastrointestinal tract of marine life and freshwater creatures, including species that humans consume. You’ll also find them in bottled water and regular drinking water, as well as in the atmosphere at large.

Dr. Manasi Agrawal, a researcher and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says that microplastics decrease in size over time.

“As [microplastics] become more and more degraded and smaller, their absorption and accumulation in different biological tissues would be higher. So there is more accumulation of microplastics when they are smaller particles,” she said. “It’s believed that nanoplastics are more harmful to human health relative to microplastics.”

Despite what scientists already know about these pollutants, more research is required to determine all their negative effects, including their effects on those with IBD.

Dr. Agrawal discusses the relationship between microplastics and IBD, including the two main factors connecting the two. She mentions the working hypothesis of intestinal inflammation being tied to higher rates of absorption of microplastics.

The Connections Between IBD, Food, & Microplastics

There is no single known cause for IBD, but because the conditions in the category revolve around gut health and the digestive tract, there is a strong connection to food and the condition’s development. What we put into our bodies matters.

“What we think is that microplastics being pro-inflammatory […] leads to intestinal inflammation and potentially may modulate the risk of inflammatory bowel disease,” said Dr. Agrawal. “And in individuals who have established IBD, presence of microplastics may lead to potentially worsening of IBD outcomes. Again, all of this is hypothetical at this point, more research is needed.”

Experts say that rises in pollution and consumption of highly processed foods across industrialized nations have contributed to IBD. But now there is increasing concern about microplastics, which are prevalent in waste management systems, food packaging, and sometimes even food itself. For example, bottled water.

A 2021 study conducted by Yan Zhang and their fellow researchers from the School of the Environment at Nanjing University in China found that higher levels of microplastics in the fecal matter of participants (both healthy ones and ones with IBD) who spent more time drinking bottled water, consuming fast-food in plastic packaging, and who had higher rates of dust exposure in their work and/or living environments. PET (which stands for polyethylene terephthalate, a kind of plastic) is the primary material used to package beverages and foods, and also breaks down into smaller plastic flakes through the wear and tear of the container. This same study also reported that the highest concentration of microplastics in fecal matter was PET.

There were also differences between the results of healthy patients and those with IBD. The ones with IBD had a higher concentration of PET in their fecal matter, suggesting that IBD patients may have more microplastics in their gastrointestinal tract compared to healthy patients. Other research into this subject shows that microplastics are present in more than 90 per cent of bottled water and that bottled water has up to 22 times more microplastics than tap water.

It’s also worth noting that food packed in plastic containers can introduce microplastics directly into the foods they hold, with an estimate of around 188 tonnes of microplastics per year released into the environment through human food consumption.

However, there are limitations to the study methods above, primarily the small sample size. On top of that, researchers remain unsure of how many microplastics are in the gastrointestinal tract and the gut, because they’re only being measured in fecal matter.

Dr. Agrawal says that while plastic containers can damage our health, some are worse than others. Different plastics are made of different chemical compounds. For example, plastics are used in both medicine and food packaging, but there’s a very big difference between the two and what they are designed to hold. To limit human exposure to microplastics, the structure of harmful plastic compounds in containers will have to be changed.

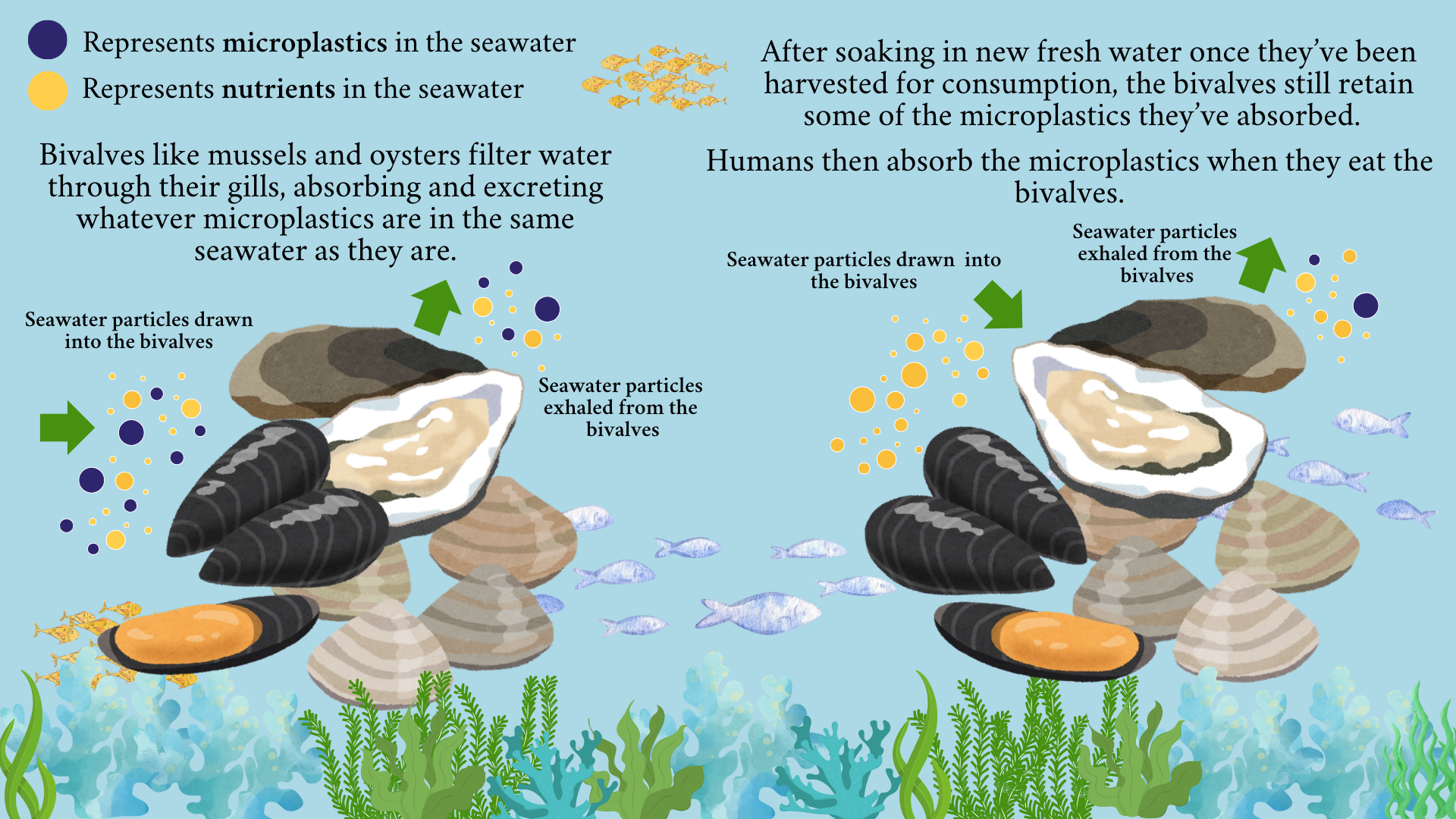

While rates of microplastics may be higher in some foods, like honey, beer, table salt, sugar, fish, shrimps, and other marine animals like bivalves, there is no specific food group to necessarily stay away from. Research conducted by scholars at the University of Victoria in British Columbia determined that there is no specific food group that has greater amounts of microplastics. More research needs to be done. But whatever microplastics are in food, end up in our bodies. For example, seafood, “through biomagnification, can often have large amounts of micro and nanoplastics, which also then go into our gastrointestinal tracts,” said Dr. Agrawal.

Dr. Agrawal and I talk about the different ways microplastics make their way into human bodies, like through ingestion and inhalation.

A United Nations report from 2016 notes that more than 800 marine animal species have either ingested or become entangled with some form of plastic in their environment, with about 220 species specifically ingesting microplastics. This includes mammals, fish, invertebrates, as well as fish-eating birds. While the plastic they consume is mainly concentrated in their digestive tract, micro and nanoplastics can also move to the circulatory system or other tissues.

The total amount of microplastics in the seafood we eat is concerning. And researchers have discovered that there is a higher concentration of microplastics in farmed mussels than in wild-caught ones.

This research also studied markets specifically in Indonesia and California and determined that there were concentrations of microplastics in wild-caught but commercially sold fish. In both of these areas, fish processed and sold from markets in the two cities have a microplastic concentration of over 20 per cent.

Scientists have also found particles of microplastics in the dried fish we eat, with around four out of 30 dried fish species having 36 out of 61 foreign particles within them identified as plastic.

Robert is conscious about the amount of microplastics in oceans and seas.

“You know, [fish are] eating little pieces of algae or whatever, and there’s a piece of microplastic there so it just goes into their mouth. And of course, for birds that eat those fish, [the microplastic particle] goes into there, it goes through the whole food chain into larger fish,” said Robert.

Robert expands on the way he thinks microplastics come into contact with humans. Seen particularly in seafood.

For some additional context, the amount of seafood consumed globally is about 17 per cent of animal protein consumed overall. And according to a report from The World Economic Forum, the global average of human consumption of seafood totalled about 20.5 kilograms per person in 2019 — that’s billions of kilograms of seafood consumed globally.

Investigating The Impacts Of “Invisible” Microplastics

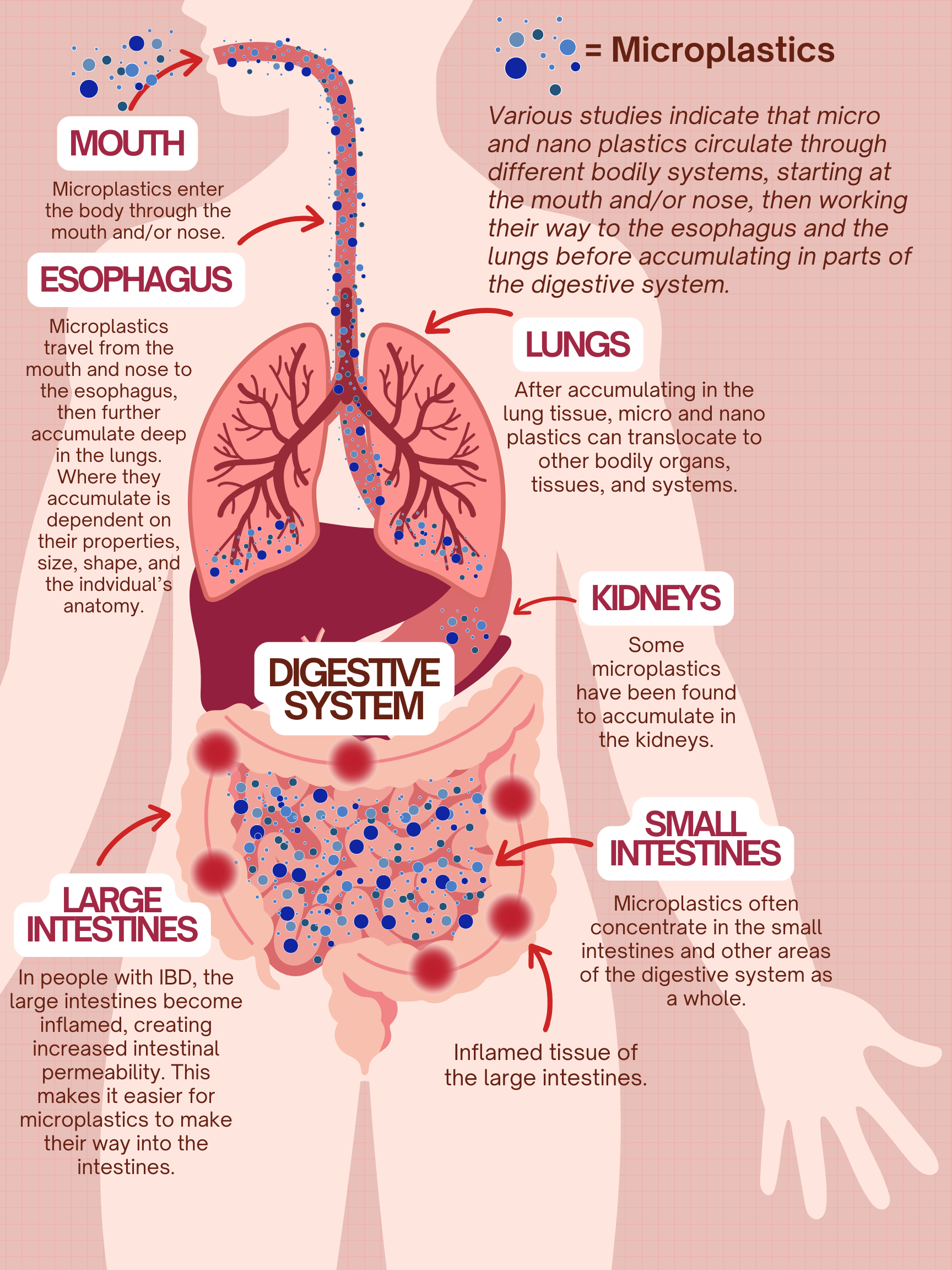

Microplastics are even in the air we breathe. Researchers say inhalation of microplastics, particularly via dust, is one of the most common ways these kinds of “invisible” microplastics enter our bodies.

One person can inhale up to twenty-two million micro and nanoplastics per year. This does not account for the microplastics that make their way into our bodies through other avenues like ingestion. The ones we inhale pass through our bodies and often accumulate in our lungs, but can also reside in the circulatory system, respiratory system, and, of course, the digestive system and digestive tract.

There are six steps in the plastic lifecycle: production, transportation, use, disposal, further degradation in the environment, and finally, emission of microplastics into our airways (along with other dangerous chemicals) from these degraded plastics. After the breakdown process, the microplastics either remain in the area or spread to new areas and environments through the air, concentrating primarily in regions in the Northern Hemisphere, despite airborne microplastics being detected on a global scale.

Zhang and researchers at the University of Nanjing in China also uncovered the impacts of dust exposure on individuals, including the differences between participants with IBD and those who were healthy. For healthy participants who were more often exposed to dust, the concentration of microplastics in their feces was about 1.8 times higher than those who were not often exposed to dust. For those with IBD in this same situation, that figure rose to 1.9.

Road dust from tires and dust from construction sites, specifically, contribute to the largest quantities of dust that contain microplastics. As a result, construction workers as well as small children are most at risk—construction workers because of the necessities of their job, and children because of the accumulation of dust on their toys, clothes, or hands that they put in their mouths. Studies show that over 900 microplastics per year may be inhaled by children through dust exposure alone.

There is also a difference between microplastics being found in the air in drier environments and wetter environments. For example, the lowest concentration of microplastics are found in the air during dry weather, but the highest during rainy weather. Some research even indicates that rain contains microplastics, In 2019 researchers found microplastics in the Pyrenees mountains, which were believed to have made their way there through rain or snowfall.

The amount of microplastics in the air also differs between urban and rural areas, according to research taken from areas around Paris, with urban areas tending to have larger concentrations of microplastics in the air compared to rural areas. Combining rainy weather with a population-dense city, therefore, means the highest concentration of invisible microplastics.

But trying to measure these kinds of microplastics can prove incredibly difficult, which is why researchers are developing new technologies to quantify them. For example, μ-Raman microscopy can identify particles of a smaller size.

“Each of these different techniques provides a different piece of information, and I think it’s putting together the composite of different techniques that’s important in understanding the impact of different aspects of microplastics,” said Dr. Agrawal. “It’s not just the number of microplastics, it’s also the shape, their chemical composition, et cetera, that is relevant to health outcomes.”

Dr. Agrawal elaborates on invisible microplastics and how difficult they are to measure and quantify.

As noted by Agrawal, though, there’s just not enough research to form any solid conclusions or set ways to measure or quantify microplastics in the air, similar to the inability to do so in the body. We know that they’re in the air and that they can prove harmful, and perhaps even a bit more harmful to those with IBD, but there’s still no clarity on their impact.

Growth In IBD Cases & Potential Connections to Microplastics

As mentioned previously, the number of people diagnosed with IBD is steadily rising in Canada. Cases are increasing across all age groups, but most swiftly and concerningly in children under the age of six. This problem extends across the world.

IBD started being diagnosed in the early 1900s in the West, paralleling the growth of industrialization in these nations, and has since increased alongside booms in manufacturing, urbanization, and all-around growth in these countries.

Dr. Agrawal discusses industrialization and how it’s connected to the development of IBD in Western nations.

A 2023 report on the adverse health effects of contaminants on IBD found that continued exposure to microplastics resulted in accelerating the development of IBD, causing a host of problems within the human body. One of these problems is how absorptive the intestine’s surface is. This makes it easier for microplastics to enter the intestines and attach to intestinal cells, which can send microplastics to different bodily systems. In animal test models, such as mice, the same thing happened. Intestinal absorption increased and altered the microflora of the intestines, which break down food.

For the mice, this increased the rate of intestinal inflammation, including the overgrowth of staphylococci, a bacterium connected to IBD. These tests on the mice show us what could be happening in our own bodies, with microplastics increasing rates of inflammation in both healthy and IBD patients.

“There does seem to be a relationship between more urbanization, industrialization, and IBD,” said Dr. Agrawal. “Whether this is specific to microplastics, or pollution more generally speaking—because there are other pollutants also that are implicated in intestinal inflammation and IBD—that is yet to be determined. Indirect evidence certainly points in that way.”

With these increases in urbanization and industrialization affecting rates of IBD, Jody says that one of her biggest fears is one of her children getting the same diagnosis that she did.

“That would just tear me apart,” she said. “I hope that they don’t have IBD or anything that I have. I think that as a parent, my whole mindset has changed—you just don’t want anything to happen to your children.”

Jody tells me about what she hopes her future looks like, including making sure her children are healthy.

Apart from pure microplastic exposure, the growth of IBD cases is also connected to the “Western diet,” with highly-processed foods, and food additives used frequently in restaurants and take-out menu items. Some scholars pose the hypothesis that not only are microplastics negatively affecting the permeability of the intestines’ surface, but so are food additives, causing increases in the rise of all autoimmune disease cases.

A Western diet, generally, includes consuming foods that are higher in fat, trans fatty acids, cholesterol, proteins, sugars, salt, and more frequent consumption of fried foods (“fast-foods”). And more people around the world are eating it. One report noted that in children the percentages of carbohydrates and sodium are, respectively, double and 20 times higher than what is recommended.

In the early days of being diagnosed with Crohn’s, Robert was able to make changes to his diet, cutting out processed foods, fried foods, and spicy foods. Instead, he opted for a homeopathic diet eating completely natural foods. It was difficult to do, but he succeeded with help from his family.

Robert tells me about the way he changed his diet after his diagnosis (pre-ostomy), including trying homeopathic diets.

The combination of living in highly microplastic-polluted environments, like cities, and eating foods that are either highly processed or come in plastic packaging doesn’t necessarily mean you will get IBD. But certain people might be more impacted by these factors.

Long-Term Health Effects of Microplastics: What Do We Know?

Research on climate change shows extreme weather events, such as increased rainfall, severe drought, and glacier thawing, will increase the amount of microplastics released into the environment, especially in aquatic habitats. However, in terms of IBD, analyzing the patterns that we see in current studies and trends is our best indicator of what comes next.

Dr. Agrawal says that while there are no current studies examining the long-term health effects of microplastics on individuals with autoimmune diseases, previous studies give some insight.

A 2024 study on microplastics in cardiovascular events by Raffaele Marfella and their fellow researchers from Italy found that in patients who have carotid artery plaques, caused by carotid artery disease, microplastics made up a specific proportion of these plaques. These patients were also more at risk for negative health developments in the long term.

Dr. Agrawal elaborates on the Marfella study.

Both Zhang and Marfella’s studies indicate that people who have higher levels of microplastics in their bodies are more likely to have a pre-existing health condition. What this means for them in the long-term, however, is still largely unknown.

Other research on the rare minnow gives us some idea of what the long-term effects could be, although it’s important to remember we’re discussing an aquatic organism, not a human.

Researchers found prolonged exposure to microplastics could potentially lead to inflammation in different parts of the fish’s gut. Changes were also found in the minnow’s immune system and stress levels, with overall long-term exposure leading to biological changes in the fish’s immune system and inflammation rates. Similar conclusions were drawn during tests with zebrafish and other aquatic organisms.

If these organisms have such negative reactions to microplastics within their systems, then humans might too.

However, there are no confirmed long-term effects of microplastics in the human body, only trends and patterns that have been established. In a 2023 National Geographic article, several experts, including Janice Brahney, a biochemist at Utah State University, confessed to fears about how little we know about microplastics and plastic pollution, despite the continued increase in plastic production.

“It is alarming because we are far into this problem and we still don’t understand the consequences, and it is going to be very difficult to back out of it if we have to,” she said.

Although cause and effect hasn’t been determined, there is an established connection to chronic diseases, like IBD.

To combat microplastics’ widespread exposure, multiple researchers have suggested implementing stricter regulations on disposing of and using plastic so heavily in our everyday lives, something that has to occur at the systemic level in order to truly make a difference. They also say microplastics should be consistently and properly measured and monitored in food, water, and air, including finding more advanced ways to treat our waste and filter our water. It’s also important to properly educate ourselves about making smarter dietary choices and being aware of the state of our environment. These are all basic measures, but they are crucial.

It’s also just the beginning.

What Happens Next?

The common thread in every study referenced here is that more research is needed to determine the full connection between microplastics and IBD. We need more studies on human participants, particularly participants in different age groups and socioeconomic standings, and especially individuals who live in different regions. Studying individuals who have different autoimmune diseases or health conditions is also necessary to understand how microplastics affect healthy or unhealthy bodies.

The research is currently in its baby stages, but the important thing is that scientists and governments are starting to pay attention. The problem of microplastics in the human body is largely connected to plastic pollution as a whole, and the more energy and resources that are put towards combating it, the closer we get to more nuanced studies of microplastics and their health risks.

Jody gives her view on microplastics, including admitting that she doesn’t know too much about them, but acknowledging that they’re everywhere.

In early 2024, Canadian Minister of Health, Mark Holland, announced more than $2 million in funding for McGill University, Memorial University of Newfoundland, and the University of Toronto to increase the amount of research on microplastics and how they affect human health. They will specifically be looking at the impact that microplastics have on food, food packaging, drinking water, indoor and outdoor air quality, and dust exposure. This research will take place over four years, and will, hopefully, give a better understanding of microplastics and their impact on us and our environment.

There is also the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which, in 2022, adopted a resolution to develop an international and legally binding document on controlling plastic pollution, particularly in marine environments. This document will address the problem of the lifecycle of plastic in our environment, including its production, design, and disposal, and will focus on ways to control the increasing plastic pollution problem. Several sessions of the committee have already taken place, and a fifth one is scheduled for August of 2025. A compilation of the draft text of the document can be found here.

We also have ongoing research studies that are looking more specifically into microplastics and intestinal inflammation, like Dr. Agrawal’s PLANET Study.

The study’s goal is to uncover the impacts of microplastics on the gut, particularly examining the connection between microplastics, intestinal inflammation, and the gut microbiome, to determine the risk of the development of IBD and other autoimmune diseases. The study specifically looks at pregnant women and women who plan to become pregnant, with or without IBD, to effectively determine microplastic influence in the early stages of life.

Dr. Agrawal further discusses the PLANET Study, along with colleague and project manager Mellissa Picker.

“The concept of the early life period is that early life, which is defined traditionally from pregnancy until approximately the first 1000 days of life, is a period of immense immune maturation and gut microbiome establishment,” said Dr. Agrawal. “And various exposures during this period have profound effects on health outcomes later in life. In the context of inflammatory bowel disease, we have found this to be increasingly relevant.”

Results from this study could provide a significant step towards further determining the connection between microplastics and IBD.

Dr. Agrawal says that we need a more thorough understanding of the way microplastics pass through the gastrointestinal tract and how they impact systemic inflammation and immune dysfunction. This also connects to the way microplastics may increase the risk of IBD, and specifically what kinds of microplastics may influence that risk.

Robert is hopeful that with the continued research into the disease and further developments with medication treatments, we’re getting closer to a cure than we were over thirty years ago, back when he was first diagnosed with the disease.

Understanding exactly what types of plastic are harmful, or more harmful than others, is another key part of the research, since there is a wide range of plastics and the different chemicals that they’re made of. If we know which ones are more harmful, we can replace them with ones that are less, particularly when it comes to things like food packaging.

Different environments result in different concentrations of microplastics in our airways. We also know that they’re found in the majority of food packaging and drinking water, in road dust, seafood, honey and table salt. Understanding where they are is great—now we know where they need to be removed from. Governments and world nations are starting to pay attention. It’s a step in the right direction, even if we have many more steps to go.

Microplastics are a growing problem, especially in terms of the environment and human health. The connection that they hold to IBD isn’t confirmed, but we do know that microplastics affect healthy and unhealthy people differently, and may significantly contribute to intestinal inflammation in both humans and animals.

The number of IBD cases will continue to rise, and I don’t think solving the problem of microplastics will solve the problem of autoimmune diseases, but experts say it’s worth it to pay attention to the connection between the two. Our bodies and our world are on the line.